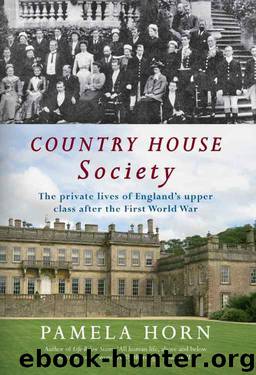

Country House Society by Pamela Horn

Author:Pamela Horn [Horn, Pamela]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: 1930's, 1920's, History, England, Aristocrats

ISBN: 9781445603186

Publisher: Amberley Publishing

Published: 2013-11-26T00:00:00+00:00

5

Domestic Affairs and Breaking the Mould

No one who considered herself a lady expected to have to do any housework. If one had a servant at all one did not even pull a curtain or open the front door when the bell rang.

Loelia, Duchess of Westminster, Grace and Favour (London, 1961), p. 94.

The upper classes now began, almost as a matter of course, to go into business. Only thus could they save the fortunes of their class.

Patrick Balfour, Society Racket: A Critical Survey of Modern Social Life (London: 1933), p. 78.

Domestic Issues

During the 1920s the domestic life of many elite families underwent a change, as they moved away from the elaborate and lavish arrangements that had been common before 1914 towards a more cautious and cost-conscious existence. For some that meant from the middle of the decade the purchase of new, more functional art deco furniture and fittings, with their rectangular shape and avoidance of excessive ornamentation, which made them easier to clean. They appealed to those consciously seeking a more modern image or who were now living in mansion flats rather than their own large houses. They were also a response to the approaching era of mass-production and the machine age.1

Very often the changes were accompanied by a reduction in the number of domestic servants, to match more restricted incomes, and a greater resort to labour-saving devices and commercial services. These latter included an increased use of hotels and restaurants as venues for luncheons, dinners and receptions by hosts and hostesses whose own domestic resources were too limited to provide large-scale hospitality. The nouveau riche also appreciated the facilities they offered since such locations removed the uncertainties involved in organising their own parties. At the Savoy, Stanley Jackson described ‘a new-rich ostentation’ jostling ‘the remains of Edwardian magnificence’. He claimed that during the decade the hotel’s fourteen banqueting rooms were continuously booked for an endless series of luncheons and dinners. ‘Throughout the ’twenties it was rare to see fewer than seven or eight hundred people in full evening dress, dining and dancing every night at the Savoy.’2

Few with straitened finances were as fortunate as Lady Diana Cooper, who was able to rely on rich friends to provide game, salmon and champagne for the lavish parties she and her husband, Duff, held at their Gower Street home. ‘Immense expenditure in effort, frugality in money, was Diana’s rule’, it was said, and ‘the result gave happiness to everyone, including the donors’. Like many successful hostesses, she was fortunate in having an exemplary butler, named Holbrook. Though, ironically, she was sometimes angered by ‘the bland satisfaction’ with which this paragon anticipated her requests. ‘We need some more coal, Holbrook’, she would say, only for him calmly to respond, ‘I took the liberty of ordering it this morning, my lady.’3

In other cases hostesses economised by organising cocktail parties, which became part of the London social scene from about 1922, or they arranged afternoon games of bridge. However, in the case of bridge enthusiasts like Margot Oxford, expenditure on the game could far outweigh economies made elsewhere.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Civilization & Culture | Expeditions & Discoveries |

| Jewish | Maritime History & Piracy |

| Religious | Slavery & Emancipation |

| Women in History |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32527)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31928)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31916)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(18998)

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(14346)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13292)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12003)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(5346)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5200)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5070)

Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow by Yuval Noah Harari(4890)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(4743)

Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl(4555)

The Silk Roads by Peter Frankopan(4512)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4447)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4189)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4080)

The Motorcycle Diaries by Ernesto Che Guevara(4069)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3940)